Through New Castle, to Freedom

James Lindsey Smith's Path to Liberation & A Modern Memorial of his Journey

In the Spring of 1838, three men from northeastern Virginia shook off the bonds of slavery and set out for freedom in the northern states. One of those men was James Lindsey Smith, whose later autobiography records their journey in fascinating, and sometimes terrifying, detail. On that route, New Castle was an important stop.

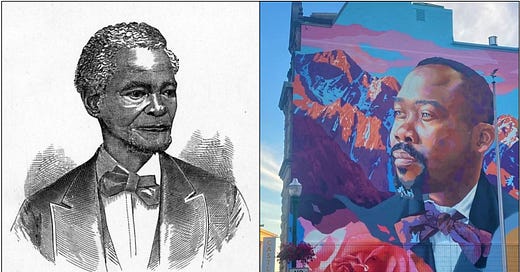

In the Spring of 2022, a group from Castle Church in Norwich, CT - where Smith ultimately settled and became a leader in the Black community - retraced the route of Smith’s “escape from slavery using his autobiography as a guide,” according to Rev. Adam Bowles, who led the walk of remembrance. The church has also created a large mural honoring Smith in Norwich’s Jubilee Park as part of its “vision to transform a blighted courtyard into beautiful community space… that celebrates resilience.”

Smith’s Life and Legacy (A Very Brief Bio)

James Lindsey Smith, who often went by Lindsey, was born on a plantation in Heathsville, in the ‘Northern Neck’ of Virginia, around 1816. Injured at a young age by falling timber crushing one of his knees, Smith was refused medical attention by his family’s ‘master,’ Thomas Langsdon. However, his mother, Rachel, secretly took her son to the doctor to learn what treatment she could to reduce complications. Over months, Smith recovered, though he would be ‘lame’ for the rest of his life.

Unable to work in the fields, Smith worked in the Langsdons’ home for a while as a young man, until Thomas died. Over the following years, he would move about a lot, living with his mother until her passing. Eventually, a new ‘young master’ in Heathsville had Smith trained as a cobbler and set him to work on his behalf in a shop there. Smith took to the work, making the shop successful and gaining skills that would serve him for life. It was during this time that he became more aware of and involved in the underground religious life of his community.

Smith’s recollection of the aftermath of the Nat Turner Rebellion is especially interesting:

When Nat. Turner's insurrection broke out, the colored people were forbidden to hold meetings among themselves. Nat. Turner was one of the slaves who had quite a large army; he was the captain to free his race… We used to steal away to some of the quarters to have our meetings. One Sabbath I went on a plantation about five miles off, where a slave woman had lost a child the day before, and as it was to be buried that day, we went to the "great house" to get permission from the master if we could have the funeral then. He sent back word for us to bury the child without any funeral services.

The child was deposited in the ground, and that night we went off nearly a mile to a lonely cabin on Griffin Furshee's plantation, where we assembled about fifty or seventy of us in number; we were so happy that we had to give vent to the feelings of our hearts, and were making more noise than we realized. The master, whose name was Griffin Furshee, had gone to bed, and being awakened by the noise, took his cane and his servant boy and came where the sound directed him. While I was exhorting, all at once the door opened and behold there he stood, with his white face looking in upon us. As soon as I saw the face I stopped suddenly, without even waiting to say amen.

The people were very much frightened; with throbbing hearts some of them went up the log chimney, others broke out through the back door, while a few, who were more self-composed, stood their ground.

Furshee did not break up the meeting or report those gathered that night to their ‘owners,’ wanting only to find out if they “were plotting some scheme to raise an insurrection.” But the clampdown continued throughout Virginia. And the constant threat to his community’s religious freedom ultimately weighed as heavily on Smith as the casual cruelty and callousness he had known his whole life.

So, around Christmas 1837, Smith began making plans with two fellow enslaved men - Zip and Lorenzo - to run away. After a setback that winter, they put their carefully-crafted plan into motion on May 6, 1838. After shaking their respective owners’ attentions for the morning through clever deception, the men met at Zip’s cabin home and headed to the Cone River to set off for freedom by canoe.

After a short trip to another plantation, the trio managed to ‘capture’ a small sail boat Zip knew of, which was usually well-secured but had been left unguarded that Sabbath day after “young folks had been sailing about the river.” From there, James, Lorenzo and Zip sailed for nearly two full days, amid difficult winds, across and up the Chesapeake.

Smith’s journey to Freedom would take him through New Castle, Philadelphia and New York City, before he found freedom in Springfield, MA, with the help of the underground railroad and an Episcopal minister, the Rev. Dr. Osgood:

When I had reached the wharf I stepped ashore, and saw a man standing on the dock; and, after inquiries concerning Doctor Osgood's residence, he kindly showed it to me. The Doctor, being at home, I gave him the letter, and as soon as he had read it, he and his family congratulated me on my escape from the hand of the oppressor. He informed me that the letter stated "that he could either send me to Canada, or he could keep me in Springfield, just as he thought best." He said: "I think we will keep you here, so you can make yourself at home." The family gathered around me to listen to my thrilling narrative of escape. We talked till the bell notified them that supper was ready. An excellent meal was prepared for me, which I accepted gladly, for the Doctor was a very liberal man, saying: "Friend, come in and have some supper."

In Springfield, James Lindsey Smith gained a formal education at the Wilbraham Academy, and would go on to help to found the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in that city. In 1842, he married and moved to Norwich, CT, where he continued to serve as an Episcopal minister and built a shoemaking business.

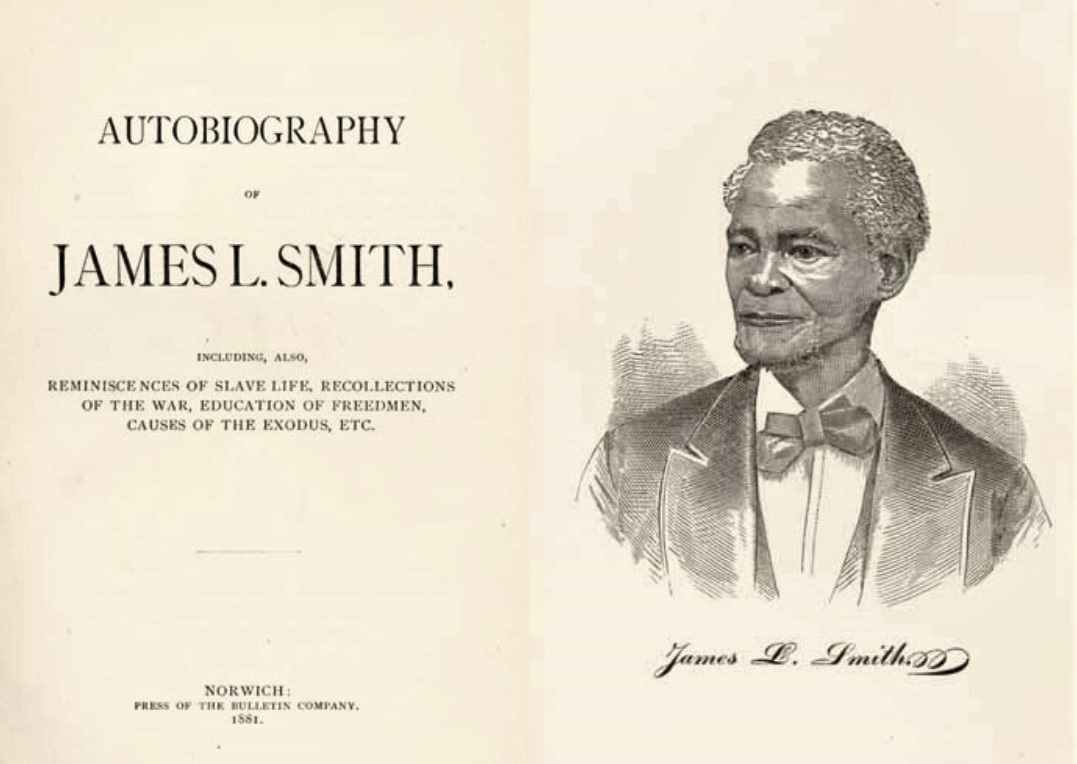

In 1881, Smith published his autobiography, sharing his recollections of slavery, escape and freedom, as well as his thoughts on the Civil War, the 15th Amendment and the issues of racism and injustice that continue to reverberate today. While Zip and Lorenzo, his companions on the road to liberty, sadly “died before freedom was proclaimed,” Smith lived well into Reconstruction.

Through dedication to his community and adopted hometown, and in his eloquent autobiography, James Lindsey Smith left behind memories and observations from which people are still learning and drawing inspiration today.

Smith’s Journey to, and through, New Castle

After their daring escape by sea, the three men “landed just below Frenchtown, Maryland,” then a tiny port town on the Chesapeake. “Zip, who had been a sailor from a boy,” Smith recalled, “knew the country and understood where to go. He was afraid to go through Frenchtown, so we took a circuitous route, until we came to the road that leads from Frenchtown to New Castle.” From there, they followed a route roughly parallel with (and in some places directly along) the Frenchtown-New Castle Railroad. Their plan was to catch a steamboat in New Castle to take them further north, to Philadelphia.

Smith’s recollections of New Castle in his autobiography are a bit mixed - that is, his knowledge of the town from the stories of other enslaved people seems almost at odds with his own experience here. He described New Castle as “one of the worst slave towns in the country, and the law was such that no steamboat, or anything else, could take a colored person to Philadelphia without first proving his or her freedom.” The town’s “very atmosphere,” he said, “seemed tainted with slavery.”

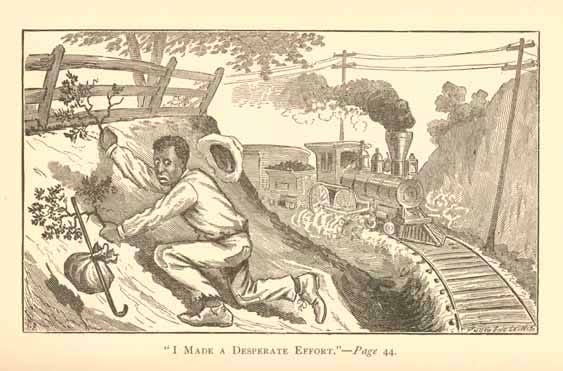

Yet for himself personally, New Castle would offer deliverance. After being left by his companions due to his lameness and slower speed, on the morning of May 8, Smith “heard a rumbling sound that seemed to me like thunder.” Terrified, he “made a desperate effort, and by the aid of the bushes and trees which I grasped, I reached the top of the bank,” collapsing to the ground as a locomotive - the first he’d ever experienced - rumbled by like “a devil… about to burn me up.”

He thought he was done-for and prayed for the end to be swift, ready to give up… yet he got up and kept going. Next coming to a house just outside town, after two days without eating, Smith felt compelled to risk re-capture in order to ask for food. Yet fortune had put a kind family in his path, and Smith expressed relief at simply having been treated like a hungry human being. In exchange for a quarter, the wife gave Smith a hearty breakfast at the family’s table, during which he and the husband talked about his travels.

After reuniting with his companions in New Castle, Smith was again pleasantly surprised when getting on the steamboat proved much easier than anticipated. “What makes it so astonishing to me,” he wrote “is that we walked aboard right in sight of every body, and no one spoke a word to us. We went to the captain's office and bought our tickets, without a word being said to us… We arrived safely in Philadelphia that afternoon.”

A Walk to Remember James Lindsey Smith…

and How Modern New Castilians Can Get Involved

Smith’s road to freedom and his legacy of leadership in the Black community are still remembered today, especially in Norwich, Connecticut, where his family’s home has become a stop on the local Freedom Trail. On the anniversary of Smith’s May 6 escape, Rev. Adam Bowles and members of his Norwich congregation began ‘James Lindsey Smith - the Journey Toward Freedom,’ a multi-day memorial trek of the path described in Smith’s autobiography.

“The purpose of ‘James Lindsey Smith - The Journey Toward Freedom’,” writes Rev. Bowles, was “to feature Smith's humanity, particularly his spirit of resilience in the face of tremendous risks and obstacles, and stir empathy for such struggles today. On [May 8,] day three of the four-day journey, [we approximated] his walk from Frenchtown MD to New Castle, DE.” This leg of the trip featured “the moment Smith nearly gave up. Nevertheless, he pressed on toward freedom.”

Locally, James Meek helped Rev. Bowles’s group to chart their course through New Castle and to connect with local volunteers. Meek, who recently moved away from New Castle after many years as a local historian and leader, created an entry for James Lindsey Smith and the upcoming ‘Journey Toward Freedom’ on the website of NC-CHAP. The page also offers some of the local details of Smith’s story, describing the autobiography as “very readable, [providing] insight into the kindly help many people provide him and the ultimate home and life he achieved.”

In the preface to his autobiography, Smith wrote: “I hope this work may find its way into the homes and hearts of those who are endeavoring still to help us in our efforts for liberty; if I succeed in this, it is all I desire. That I may have the prayers of all who are interested in my behalf, is the earnest desire of the writer.” Smith did succeed, his words echoing down through generations to today’s Americans as we continue to learn what it means to seek freedom, and to be free.

Request for Volunteers

Jim Meek is seeking help ahead of the event from locals who might be willing to scout parts of the route between Frenchtown and New Castle. While the entire 18-mile leg will not be walked, he hopes to identify portions that can safely be traversed by participants on May 8. Meek is looking for a few adventurous - but safety-conscious - spirits willing to do some pathfinding. Those interested should check out the general plan and options on the web page and email Mr. Meek.

This article was originally published prior to the memorial walk, and has since been updated. The walk has come and gone, but readers can still check out Jim Meek’s map of the route below.