Two hundred years ago this month, on April 26, 1824, nearly two dozen buildings on The Strand, then called Water Street, burned to the ground in what would become New Castle’s own ‘Great Fire.’ Nobody perished, fortunately. Yet the destruction left over 200 people homeless, roughly a sixth of the city at that time, and many of these faced complete ruin following the loss of all of their property.

Estimates after the blaze put the property damage - which included some of the finest homes in Delaware - at approx. $100,000. That’s well over1 $3.2 million ‘in today’s dollars.’ Luckily, an outpouring of support from across the eastern seaboard helped affected families and businesses to rebuild the street - already iconic then - in the years that followed.

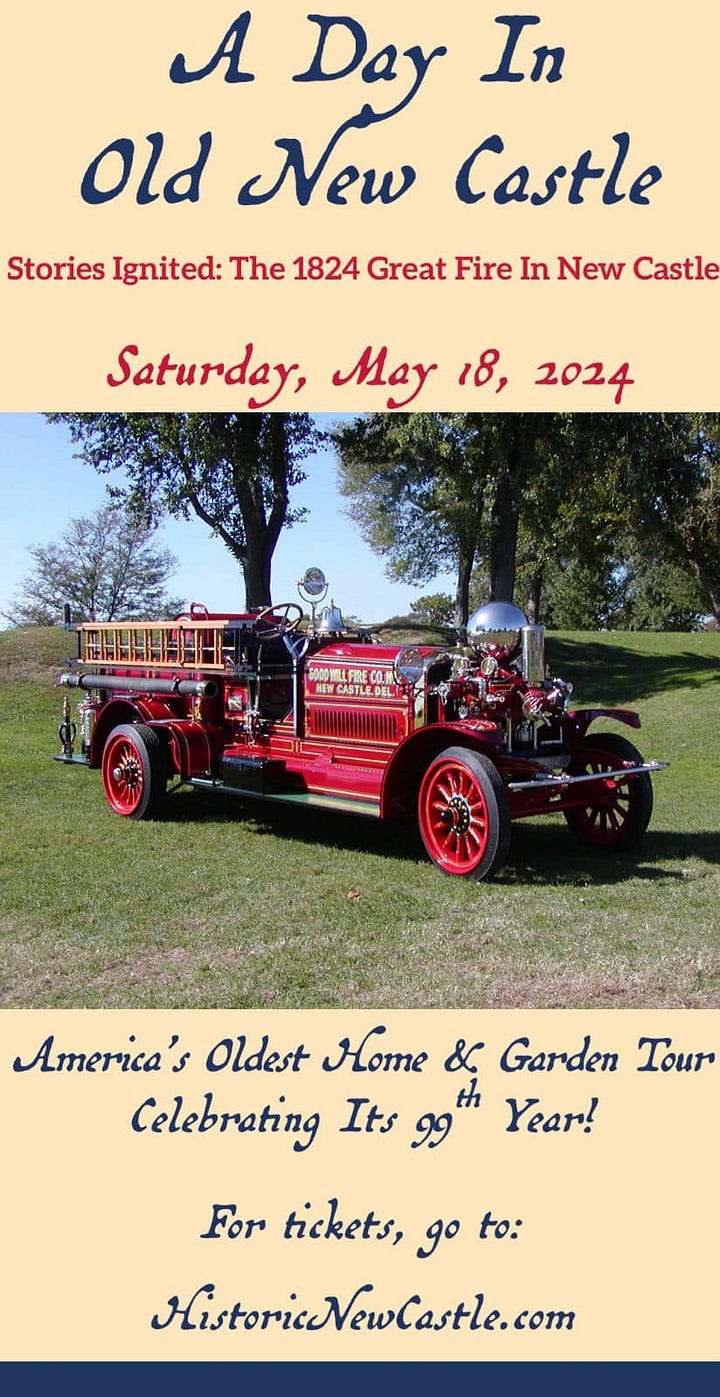

This year’s 99th iteration of A Day in Old New Castle (DIONC) on Saturday, May 18, will seek to rekindle the town’s memory of this seminal event from its history.

There are other commemorations coming too, including a lecture about the Great Fire and its aftermath by NCHS Director Mike Connolly on the anniversary (4/26), and ‘Inferno 1824,’ an art competition the city’s new Outreach Team is hosting during DIONC. With so much promising to heat up New Castle’s Spring event season, here’s a look at some of the history it’s based on…

Before the Blaze: Small Town, Big Ambitions

At the beginning of the 19th Century, New Castle was a small but bustling city. Though the state capital had moved away, it remained the county seat and the legal center of northern Delaware. Several founding families, statewide luminaries, and a large number of attorneys lived in town, many on the streets closest to the river.

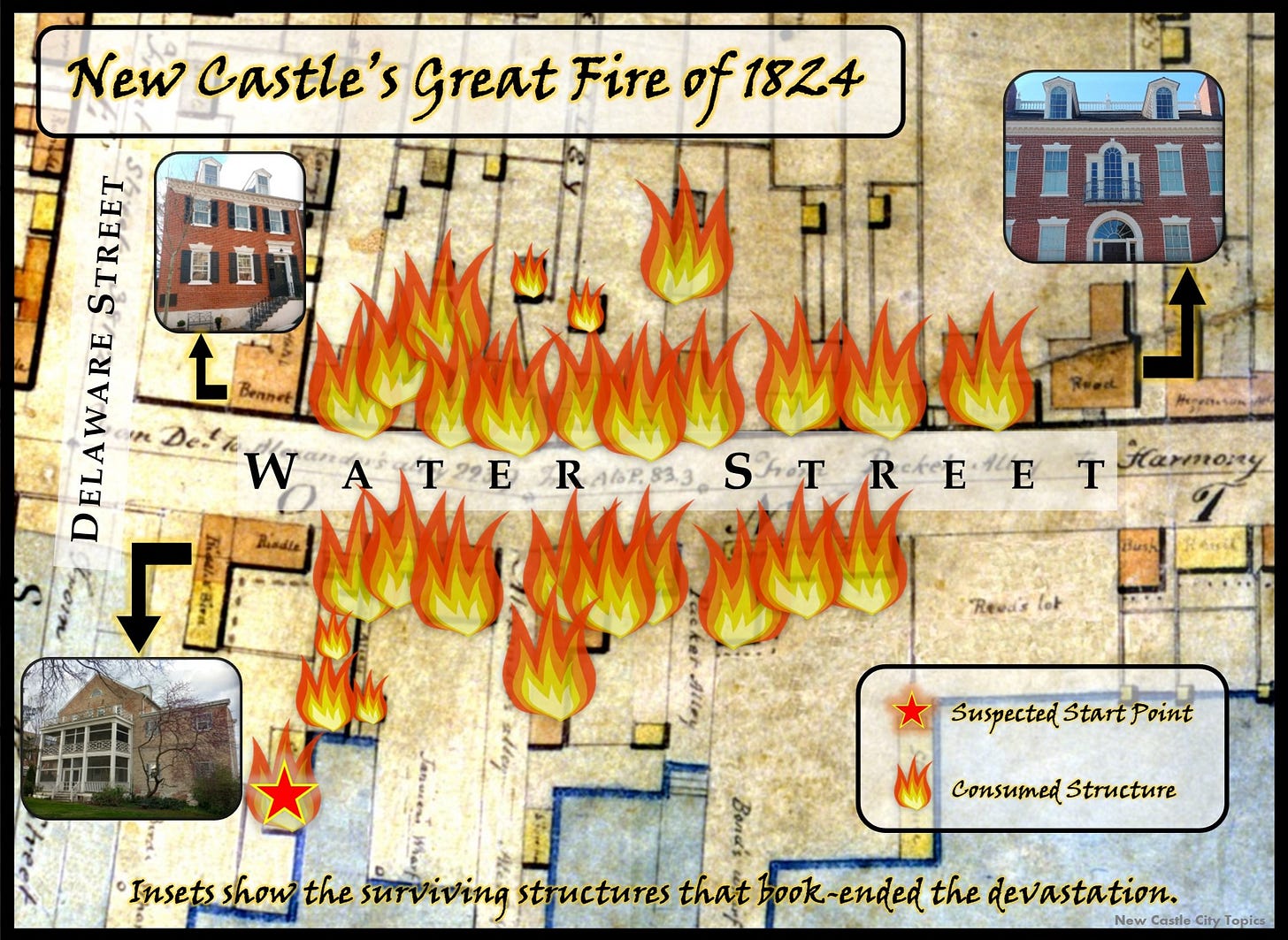

In 1805, Benjamin Latrobe completed his famous Survey of the town, showing the street we know today as The Strand as ‘Front Street.’ By the 1820’s, it had been renamed as ‘Water Street,’ which is what appears in most concurrent accounts of the Great Fire. In later years, it would become ‘Front Street’ again before finally being renamed as The Strand in the 20th century.

The home of George Read I, a Signer of the Declaration - was among the road’s crown jewels, famous among early US elites for its hospitality and considered “one of the finest family residences in the South.”2 Next door, the newer, Federal-style home of his son, George Read II, was turning heads as one of the largest houses in the state at the time.

While the city’s riverfront and center were somewhat upscale and even cosmopolitan, like most of the country at that time, New Castle was largely an agrarian community, and not especially wealthy. Over a quarter of the working age population was employed on farms, with less than 5% in commerce or manufacture, according to the U.S. Census of 1820.

The town’s total population in that accounting was 2,671.

Of those, 161 were enslaved people, many of whom would have lived and worked among Water Street’s bustling businesses and estates. A recent presentation by UD post-grad Melissa Benbow in collaboration with the Delaware Historical Society documented many of the Black families who may have been impacted by these events, though accounts of the fire from the time do not share their stories.

During the War of 1812, federal soldiers and munitions had been stationed in The Arsenal. According to the New Castle Historical Society, “the building remained a military storehouse even after the War of 1812 ended [and] finally ceased to be used for munitions storage in the late 1820s.”

So county, state and federal business were all coming through New Castle as Winter gave way to Spring in 1824. Its port was a popular stop along the Delaware River between Philadelphia and the Atlantic. Though small, the town had long been ‘punching above its weight,’ politically and culturally, and its ambitions were even bigger than some of the fine houses on Water Street.

From Innocent Beginnings, a Catastrophic End

It was a cold Monday afternoon in April - clear, but with a very strong and persistent wind blowing north along the Delaware River. Farmers were preparing or planting their fields. Cases were being heard at the Court House. The steamboat Superior was approaching town with passengers from Philly. Innkeepers were turning over rooms for the day. And most children were at school in the Academy building…

But not little John Roberts and Dick Riddle.

Whether the two young friends were playing hooky or just not enrolled isn’t clear. Their main concern that afternoon was with the shivering puppies in their care, and how to warm them up. At the southern end of Water Street, in the stable belonging to Dick’s father, innkeeper James Riddle, they decided to start a small fire. (Some accounts place the epicenter in a nearby shed belonging to Jeremiah Bowman.)

Wherever the fire started, the boys soon lost control of it, as the day’s fierce winds carried embers or full-fledged flames to Mr. Riddle’s stable… and, even more disastrously, to Mr. Bowman’s lumber yard.

In just minutes, both fire-prone structures were ablaze, with continuing gales rapidly threatening further spread.

Citizens quickly raised the alarm, calling for both of the volunteer fire companies then operating in the city. The Union Fire Co. had formed in 1797. The Penn Fire Co., formed just a few years earlier in 1820, had recently acquired a then-modern pumping apparatus.

Nonetheless, the flames quickly spread, engulfing neighboring homes and stores. As structures began to burn, their inhabitants started dragging what they could save out into the street. Arriving on the scene, the fire companies quickly lent aid and began to fight the spread.

The aforementioned schoolchildren, hearing the hue and cry shortly after 3pm, bolted from the Academy and down Read’s Alley to investigate the commotion. One of these, twelve year old Sarah McCullough, would later leave behind some of the most vivid recollections of this event that survive, sure to be featured at A Day in Old New Castle!

Local firefighters’ and citizens’ heroic efforts would, sadly, prove unequal to the task of containing the conflagration, as the driving wind soon carried a fateful spark across Water Street. Homes and businesses - including a tavern, hotel and bakery - were rapidly ablaze on the western block as well.

The flames continued northward, now spreading along both sides of the once-placid Water Street. Caught in the crosswinds, the very furniture and belongings that had set there for safety soon burned as well.

When he recognized that, as one contemporary report put it, “the fire had made such progress as to present an ungovernable appearance,” Sheriff David C. Wilson mounted up and rode with all haste to Wilmington for the aid of its various fire companies.

Wilmington’s fire companies responded immediately, making the 6-mile journey with their apparatus in “Little more than half an hour” after they received word, according to a later commendation. After its passengers from Philadelphia disembarked, the Superior also helped to ferry people and equipment between New Castle and Wilmington.

By the time help arrived, homes up and down both sides of street were fully engulfed in the rising flames. Fire had spread as far as the George Read I house on the land side of the street, while ‘Read’s lot’ along the water on the opposite side had thus far worked as a firebreak.

Firemen quickly focused their efforts on preventing any further spread, including to the George Read II house, which stood mere yards from that of his father. Fortunately, their work, the wide gap in structures offered by Read’s waterfront lot, and the newer Read House’s effective brick firewall, kept the fire from continuing any further north.

Yet the inferno raged on, consuming the structures it had already claimed almost entirely.

Ultimately, it was no human effort but an April shower that put out the Great Fire, the last of its flames rising into twilight as sizzling raindrops filled New Castle’s traumatized downtown with steam and smoke.

Amid the Ruins: Aftermath

At the end of this catastrophic day, twenty three dwellings or businesses had been gutted, hundreds of people made homeless, and an unknown treasury of personal belongings and effects destroyed.

As noted at the top, the monetary value of the real property lost was staggering - millions of 2024 dollars. However, this does little to convey the true scope of the loss at a time when there was no social safety net.

Even for families fortunate enough to own their property, the damage was near-total, with only whatever furnishings they’d salvaged and the value of their land remaining. Only one of these, the Janviers, had fire insurance - a relatively new product at the time. Many people were left “without even a change of wearing apparel,” according to the report of a meeting held by residents six days after the fire.

Per that same report, eight shopkeepers had lost their entire stock, and eight mechanics their furniture, inventory and tools. Three inkeeps had no inns to keep, and “twenty-three families have been deprived of every thing that was essential to domestic comfort.”

The map below uses the 1805 Latrobe Survey map of the street to show the trail of fiery devastation, indicating which structures burned, and inset with modern photos of those that did not.

The fire and its immediate aftermath were vividly recalled in a letter penned at 2am on the same night the fire had just subsided, by Maria Rogers, a woman in her late 30’s who lived at 214 Delaware Street:

You can have no idea of the scene of horror it exhibited. Imagine the whole on fire… all the back buildings on both sides of Water Street, the females crying, and yet very actively engaged in carrying water. I am almost exhausted with fatigue. I have been carrying water, and furniture, all the afternoon - the furniture is lying about in the streets, the market house filled, the arsenal, and almost all the street the market house stands in, some in the meeting house, and in the churchyard…

… And yet we have reason to be thankful, that no lives were lost.

The names of those who lost their home or business, in addition to the Riddles, Bowmans, Reads, McCulloughs and Janviers already mentioned, included Ritchie, M’Calmont, Sexton, Raynow, Steele, Barneyby, and others, as well as the Union Line Steam Boat Company.

The town quickly rallied around those whose lives were upended by the fire. According to reports from the time:

On the very night of the fire, everyone had a place to sleep safely, as neighbors took in all who had been left without a home;

A local committee was formed to collect aid for those affected, from fellow townsfolk and from abroad. These included Thomas W. Rogers, David C. Wilson, John Moody, Henry Colesberry and Nicholas Van Dyke; and

Captains of steamships coming through New Castle in the following weeks were urged to take up collections to help.

Within days, news of the fire had spread far and wide, propelled by both the magnitude of the catastrophe itself and the notoriety of many of those affected. Stories in papers up and down the East Coast told of “the most tremendous and destructive fire, that ever occurred in Delaware,” a “calamity unparallelled.”

As word got out, support began to pour in. In cities around the country, from as near as Wilmington and Philadelphia, to as far as New York, Boston, Lancaster, PA, and Frenchtown, MD, collections were taken up to assist “the New Castle sufferers.” In the federal district, the Honorable Louis McLane even collected $565 from his Congressional colleagues.

All of this, as well as contributions from banks and corporations in Delaware in neighboring states, flowed through the citizens’ relief committee.

While Mrs. Janvier’s fire insurance would pay out over $1200 to help rebuild her family’s home, many were dependent upon the aid provided. The clean-up needed after the fire was extensive, on top of which people had to either rebuild or find new (rental) accommodations, and restore their most basic personal belongings.

Thankfully, that does seem to have been there for most, with updates months later indicating that all had been rehoused, at least temporarily. With community support and mutual aid, the victims of the Great Fire began picking up the pieces of their scorched lives and looking to their - and New Castle’s - future.

From the Ashes: the Great Fire’s Legacy in New Castle and Beyond

With aid from around the country and a community eager to pitch in, rebuilding of New Castle’s densest and busiest neighborhood got under way rapidly.

In New Castle, Delaware: A Walk Through Time, authors Barbara Benson and Carol Hoffecker analyzed the architectural shifts that accompanied the process:

Most buildings were total losses, but portions of some could be saved or salvaged and incorporated into new foundations or buildings... Rebuilding provided the opportunity to change building material from wood to brick and to reposition and even expand the size of some of the structures. Most builders and owners chose both options… No one along The Strand chose [a more modern architecture]. New Castilians clearly preferred to retain the more conservative, tried-and-true Federal style. The lovely, large Federal-style townhouse at #17, for example, rose in brick over the ruins of a frame house that had been part of a four-generation old complex of workshops and warehouses.

… Some of the buildings arising from the ashes of 1824 were designed to be businesses, and others to be business-residence combinations. Number 25 on the north side of Packet Alley always intrigues people because of the [Ivory Soap] advertisement painted on [its side] wall. From earliest days this site had been commercial - first as a tavern, then a ship chandlery, and later a general store.

Homes were rebuilt or built anew; new businesses opened; life carried on.

Water Street - renamed Front Street again not long after the fire - remained part of New Castle’s cultural and commercial center for years to come. James Riddle’s main house, undamaged by the inferno that started just behind it in his stables (or in Mr. Bowman’s ‘shanty shack’), would later become the Jefferson Hotel, which offered the city’s hospitality to travelers for many years.

The Fire had ramifications beyond the city, as well. For decades, there had been a competitive animosity between New Castle and Wilmington. Yet the latter’s deep sympathy for - and outpouring of support for - those affected by the conflagration seems to have eased these tensions.

The devastation of April 1824 also led, in February 1825, to the state legislature in Dover enacting a law to permit the town to levy a “fire tax” on citizens. The monies raised could be put toward the purchase of fire fighting equipment and the support of local fire companies.

Indeed, soon after the calamity, the Penn Fire Company invested in a new mobile pump engine that could throw water higher than the tallest building in New Castle. That apparatus was dubbed the “Good Will,” a name that lives on through the moniker of the town’s modern Good Will Fire Company, formed in 1907 through the merger of earlier volunteer companies.

By the end of the decade, the New Castle-Frenchtown Railroad would open. The first steam train in Delaware, and one of the first in the nation, its 27 miles of tracks brought even more life and business through town.3

While it was no human effort that ultimately tamed the Great Fire, neither did the fire tame the spirit of those whose lives it touched. Unbroken by the catastrophe and more unified as a town than ever before, within a few years, New Castle was back on track.

DIONC 2024 - “Stories Ignited”

There are so many more fascinating details and personal stories to be explored stemming from the Great Fire and is effects on the city.

On Saturday, May 18, ‘Old New Castle’ will open its doors to share this history - and the charming city it’s become since - with neighbors and visitors. This year’s A Day in Old New Castle is set to dive deeply into the ways that the Great Fire changed the city, and molded the community that calls it home.

Special effort has been put into recruiting residents on The Strand to open their homes that either survived the catastrophe, or rose from its ashes. Good Will Fire Company will commemorate their 100th year at the event by hosting antique fire engines and equipment, with help (and additional historic apparatus) from other companies throughout Delaware.

Free activities will include:

Children’s activities on the Green and Wharf,

Plein Air Art Competition and Sale on the Green,

Native American foodways demonstration,

Costumed reenactors throughout the town, and

Tented seating and food trucks at the Wharf.

Adult Tickets are $25 and will be required for:

Kalmar Nyckel ship tours at the Wharf,

Historic houses and gardens open for tour, and

Museums and church tours.

Visitors in Colonial or Victorian period clothing get $1 off their ticket price (if paying on site). Tickets may be pre-purchased at historicnewcastle.com.

A Day in Old New Castle 2024 is organized by New Castle Community Partnership, and co-chaired by Judith Baldini, Antoinette Maccari-Klingsberg and Cindy Snyder. DIONC sponsors include Jessops and the Farmer’s Market, while the list of event partners comprises almost every other major cultural org and institution in New Castle.

Thanks to all of them, and the large cadre of volunteers who will help bring it all together on Saturday, May 18!

Thank you for reading…

If you enjoyed this post, please help others find it with a Share on social media!

City Topics can also be found:

On Facebook,

Also our Fb-based City Topics group: locals only, zero spam.

On Instagram, and

On YouTube.

If you were forwarded this post, please consider subscribing on our website to receive more feature stories like it highlighting New Castle history, culture and events, as well as the monthly New Castle Digest.

$3.2M is the modern equivalent provided by several online calculators; however, these do not account for the value of property having risen faster over all that time than the average value of goods on which the power of the dollar over time is calculated.

Additional Sources:

Benson & Hoffecker. New Castle, Delaware: A Walk Through Time. Oak Knoll, 2011.

Michael Connolly. “The Great Fire of 1824” and “The Great Fire of 1824 (Lecture)” on YouTube. New Castle Historical Society, 2022/2023.

Delaware Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration. New Castle on the Delaware. NCHS & WPA, 1936.

Accounts from the American Watchman, Delaware Gazette, and Wilmingtonian newspapers, as well as the papers of George Read and others, as collected by the New Castle Community History and Archaeology Program (NC-CHAP.org).